SELF PORTRAIT BY ROBERT W. RICHARDS

‘Dirty’ Magazines Get the Museum Treatment

An interview with the Artist/Curator Robert W. Richards

The exhibition Stroke: From Under the Mattress to the Museum Walls on view at Leslie + Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art until May 25th, is a spectacular show of “erotic illustrations by 25 artists who made work for gay male magazines from the 1950s to the 1990s.” We were lucky enough to have a sit down interview with Robert W. Richards, the artist/curator of the exhibition. Here’s what he had to say.

Where are you from? Originally many moons ago, I’m from Maine. The southern part of Maine. Between Ogunquit and Kennebunkport, but inland. No glamour at all. Actually it was the coast. I left home very young. I was about 15.

So you moved to New York. I moved to Boston. I went to school there and then came to New York in the 60’s.

When did you first start drawing? I never didn’t draw. I always drew. I was one of those kids that stayed by themselves you know. It was either go out and play sports or stay home and color. So I stayed home and colored.

What was the subject matter of your earlier work? My very earliest work was fashion and I did fashion big time. Right up until the mid 70’s. Then I just didn’t want to do it anymore because by that time, it involved traveling a great deal. You know it was a circuit, Paris, London, Rome, Milan, Los Angeles, New York. Which was okay for awhile, it was fun but then when all the couture houses began doing ready-to-wear, they had two showings a year. So it was Paris Paris, Rome Rome, London London, and you were just never home and you lose track of yourself. You know, you meet friends on the street and they say, “Oh, you’re in town!” You say, “well I do live here,” but after awhile you realize you have to be in one place. I mean you can travel, but not 30 weeks a year.

How did you get involved curating this exhibition Stroke? After I left the fashion thing, I wanted to draw men. So I started drawing for the magazines that are in Stroke.

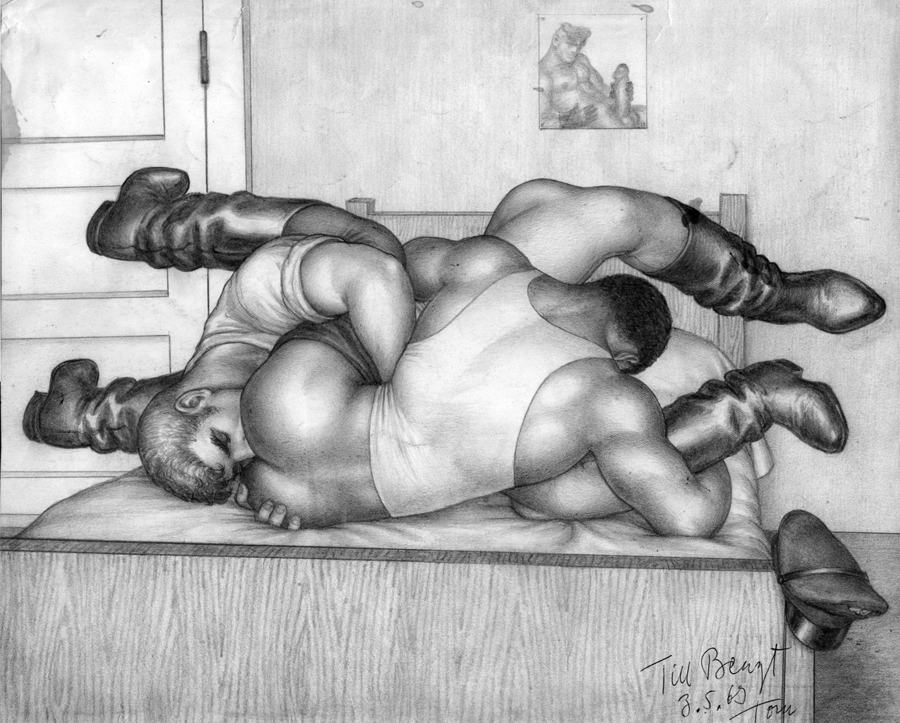

Touko Laaksonen (Tom of Finland), Till Bengt, 1963, Graphite on paper, 9″x11″. Collection Leslie-Lohman Museum, Founders’ gift. Copyright 1963 Tom of Finland Foundation.

Touko Laaksonen (Tom of Finland), Till Bengt, 1963, Graphite on paper, 9″x11″. Collection Leslie-Lohman Museum, Founders’ gift. Copyright 1963 Tom of Finland Foundation.

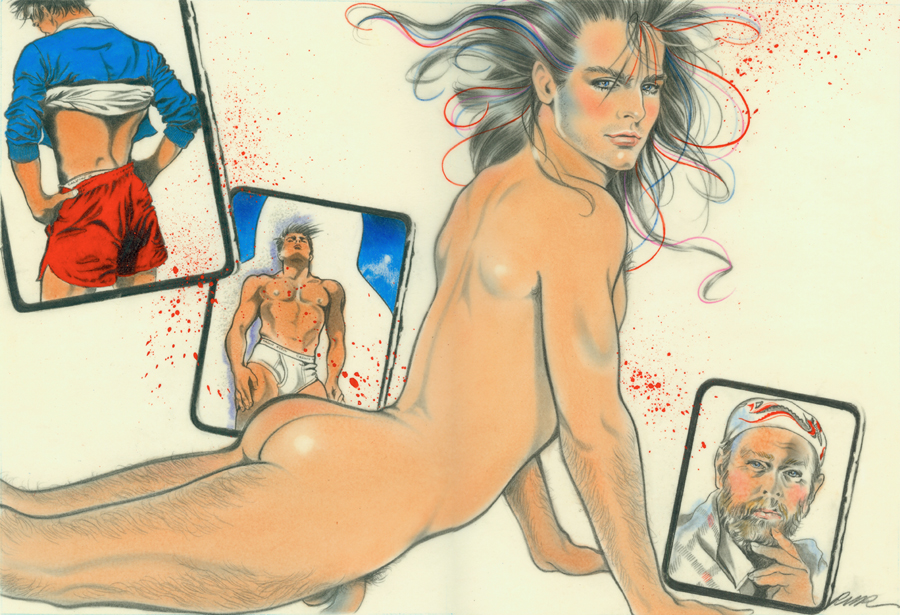

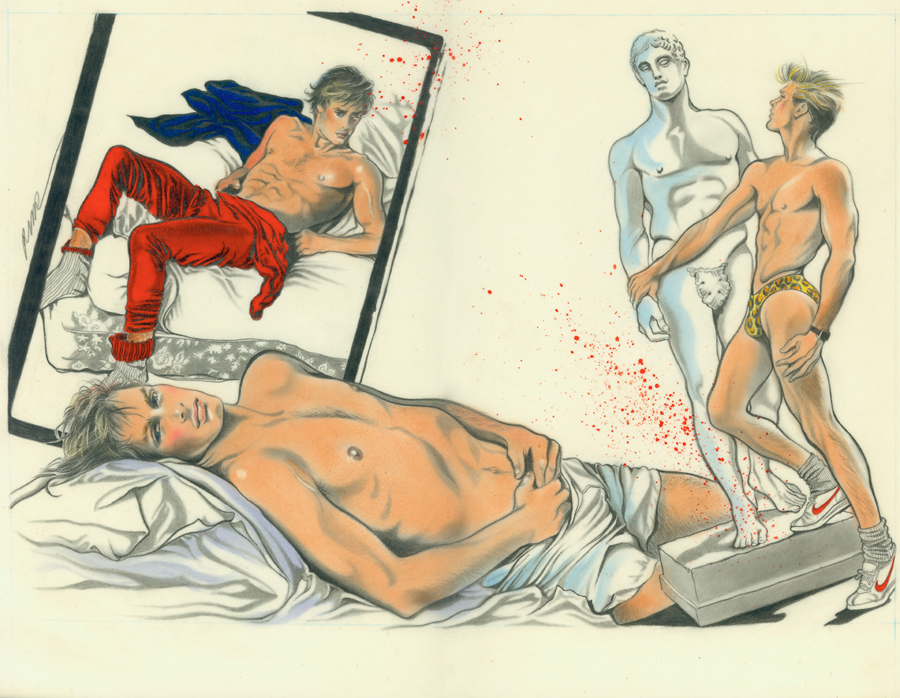

Richard Rosenfeld, Untitled, 1982, Color pencil on paper, 18.75″x24″. Courtesy of the artist.

Richard Rosenfeld, Untitled, 1982, Color pencil on paper, 18.75″x24″. Courtesy of the artist.

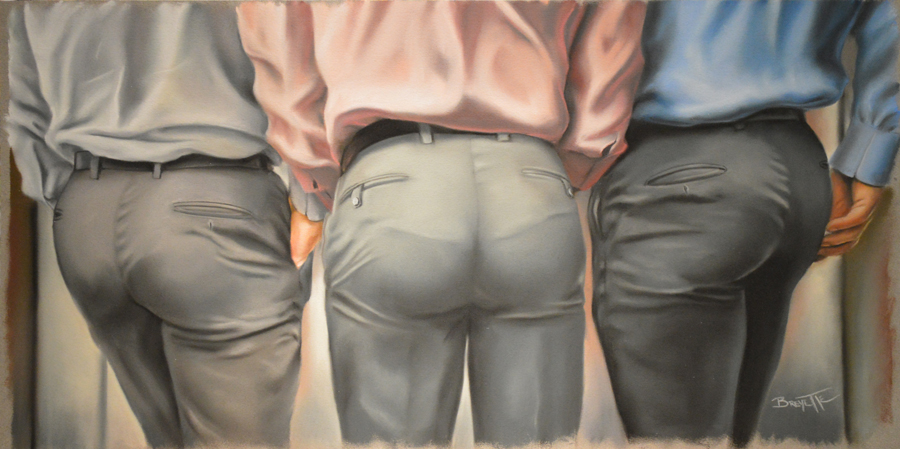

Michael Breyette, Power Bottoms, 2013, pastel on pastel paper, 11.5″x24″. Courtesy of the artist.

Michael Breyette, Power Bottoms, 2013, pastel on pastel paper, 11.5″x24″. Courtesy of the artist.

What magazines were they? Mandate, Honcho, Torso, Manshots, All Man, Advocate Men, all of them. I did up until, when the VHS came in — the videotape, the magazines started failing. Then when DVD came in, it got worse. Then when porn became available on the computer, there was no need for the magazines so they just died, which was okay. You know I had a long run. I paid my rent off with them for many years and it was fine. But from the 90’s on, all this great work by these great artists was forgotten and that really bothered me because I think people began to think that these magazines were just trash. Some were and some weren’t. But all these great artists like Antonio [Lopez], Mel Odem, Richard Rosenfeld, Benôit Prévot, all had this huge body of work and I just decided I wanted to show them. I’m on the board of Leslie Lohman, so I went to the board and I made this proposal. At first they were a little “iffy,” because they thought it was going to be a jerk-off show, which I assure you as you have seen it, it is not. It’s a beautiful show.

It’s Stunning. Thank you. Beautiful work by great artists. So that was 4 years ago that I made the proposal, so it’s been in the back of my head for all this time. And then for the last year I worked on it literally every day, because I had to find this work and I knew where to find a lot of it because I was contemporary with a lot of these people and they were still in my life. The ones that were dead, I kind of knew who had the estate. The others I just hunted down. Families were not cooperative — the artwork was under the bed in a box until that day when they decide to throw it out. In hunting I found collectors who had a lot of this stuff, so that’s how I found it. That’s my involvement in Stroke. It’s commitment really. I mean I’m barely in the show myself. That doesn’t mean I won’t have a show of my own some day, I’ve had many shows of my own but you know what I mean. It’s not about me, I only have that Toby drawing in there, because that’s the boy I created for Torso.

The guy with the long hair? Yeah, who had adventures every month and I just used that, when I do tours of the show, which I do every Saturday and Sunday from 3-5. It gives me something — just another dimension that was in the magazines because people forget it wasn’t all just boys in beige living rooms, with a hard on and a plant in the corner. There was a lot more at one time, it devolved to that. It devolved to whoever was making a movie took stills for the magazines, and no longer did shoots at the end.

Robert W. Richards, Toby Boy’s Life series, 1984, Graphite, pastel and watercolor on vellum, 13″x16″. Published in TORSO, 1984. Courtesy of the artist.

Robert W. Richards, Toby Boy’s Life series, 1984, Graphite, pastel and watercolor on vellum, 13″x16″. Published in TORSO, 1984. Courtesy of the artist.

Robert W. Richards, Toby Boy’s Life series, 1984, Graphite, pastel and watercolor on vellum, 13″x16″. Published in TORSO, 1984. Courtesy of the artist.

Robert W. Richards, Toby Boy’s Life series, 1984, Graphite, pastel and watercolor on vellum, 13″x16″. Published in TORSO, 1984. Courtesy of the artist.

So what was the criteria for choosing which artist to show? Quality. Quality was the only criteria. Absolutely. Beauty, real art, real drawing, real painting. Real quality work. A lot of it was junk and I didn’t want junk. As a matter of fact we’ve gotten a book deal on ‘Stroke.’ I can’t give you any details but we are going to expand, it’s great. It’ll be a good book. There’s never been a book that examined these artists.

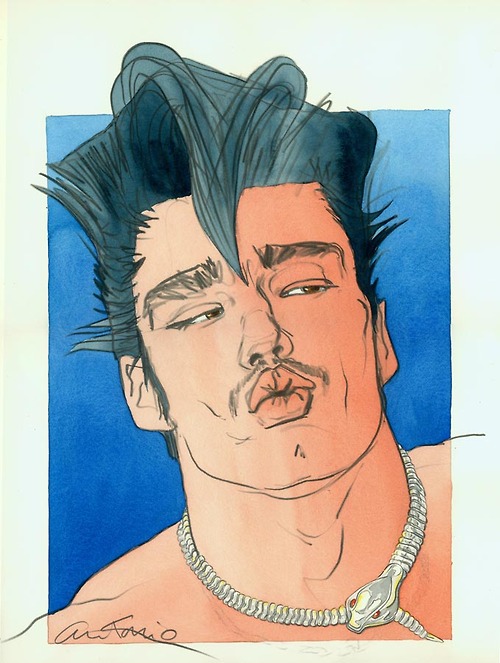

Are you drawn to any artist’s work in the show specifically? Do I have favorites? Yeah. Of course. Antonio [Lopez], actually that’s an interesting little tidbit because Antonio was the reason I didn’t want to do fashion anymore, because when Antonio came in, I knew that the next generation belonged to him and that I was the previous generation. It was time to go. Plus as I said, I wanted to draw men. I wanted to draw people, not people in clothes necessarily but I wanted emotion in my drawings. I wanted people without clothes. Where the issue was with clothes. So of course Antonio remains despite the fact that he pitched me out of the business, he remains still an idol of mine. Richard Rosenfeld who is a professor, at both F.I.T. and Parsons, those are my two favorites of the show. Mel Odem of course, the great Mel Odem, who is more famous for the work he did with Playboy and Time Magazine, because he did several Time Magazine covers. But he still did this, and I knew it.

Whose work do you feel you were influenced by, if you were to look back? Primarily a great fashion illustrator who is no longer with us, named Kenneth Paul Block. That was what I aspired to but I was also very influenced by music and other things — you know I was a kid from a small town in Maine, and to aspire to be in fashion is a little ridiculous. I was very influenced by fashion magazines. That was what I wanted. Some of it I got. Obviously I didn’t get Architectural Digest (laughs).

Can you talk about the significance of the title, the part that says “from under the mattress to the museum walls”? Because for many men, these magazines were all they had to relate to, that was gay. They would go out for the evening to a bar, to a movie or whatever and if things didn’t go their way, whatever they desired, these magazines were a very nice “date” that you could stop at the newsstand and buy, because they were distributed everywhere. The smallest towns, had these magazines and the problem was people were afraid to buy them in their own neighborhoods because they knew the drugstore guy or the newsstand guy, so they didn’t. They went across town or stole them. Which was my method (laughs), or I would buy Vogue, tuck Physique Pictorial into it, pay fast and run, I probably did this two or three times. I had to do it.

Why were you into those magazines? Desire. It’s a part of your sexuality, I’d wanted those magazines, and like everybody else I hid them. So that’s the “under the mattress,” that became a cliché — under my mattress. It’s a big journey this year, at this particular moment in gay history, for these magazines to make that journey from under the mattress to the walls of what’s now a very prestigious museum.

You mean the show at MOCA and the Leslie Lohman show. MOCA of course.

There was also a show at the NYU gallery, the Bob Mizer show. And MOMA has the Tom of Finland, but they didn’t buy them, they were donated, under condition that they’d show them, and they showed two. But if you’ve seen the show, there’s a Tom of Finland of a guy getting fucked and he’s sucking a cock, that was of course necessary to show some of that material. But strangely Huffington Post did a great piece on “Stroke”, and they showed 8 images, and they printed that one, and I thought “This is great, we are pioneers.” So, I’m not saying our problems as gay men are solved, but we are making strides in imposing our desire and taste on people. And that’s the mission of “Stroke” to free people and to realize that we’ve always produced wonderful work.

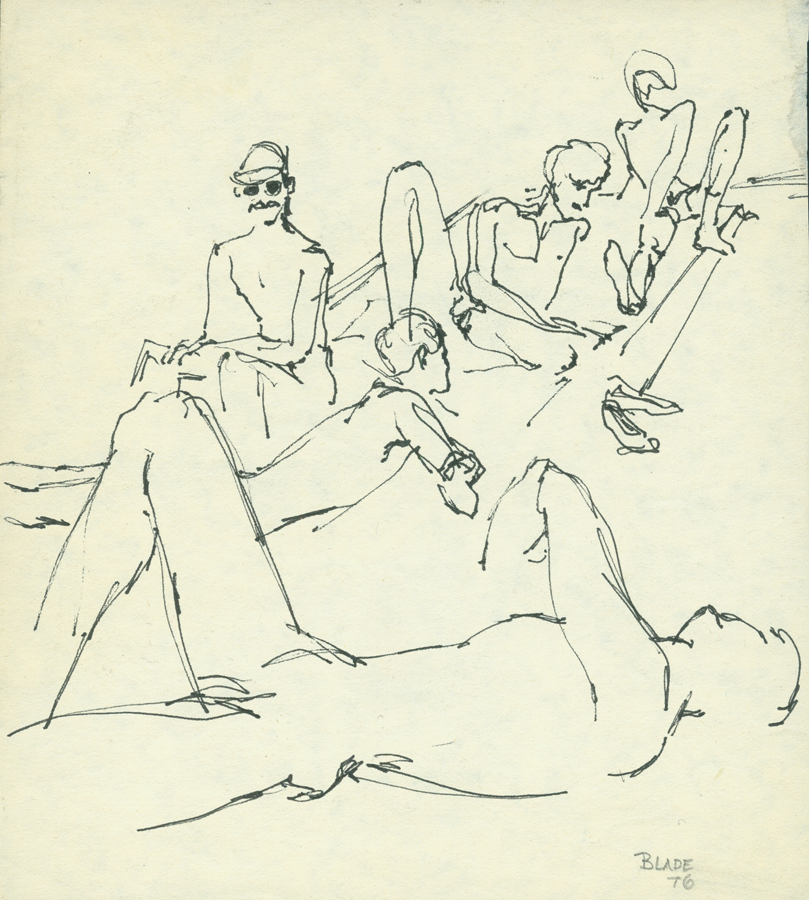

Neal Bate (Blade), Untitled, 1976, Ink on paper, 8″x7.25″. Collection of Leslie Lohman Museum.

Neal Bate (Blade), Untitled, 1976, Ink on paper, 8″x7.25″. Collection of Leslie Lohman Museum.

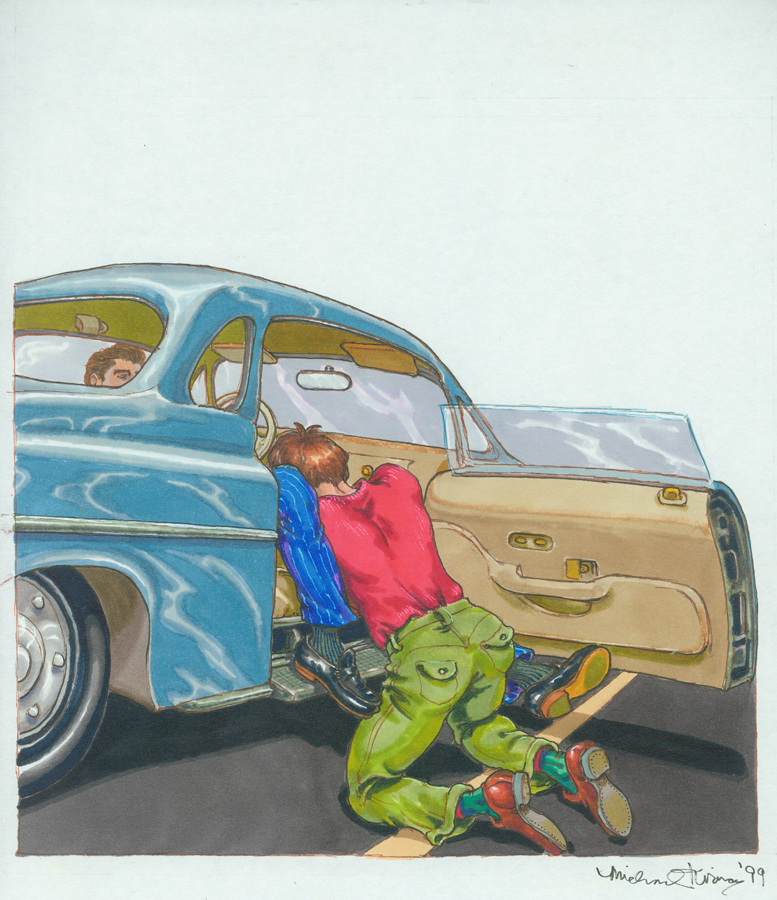

Michael Kirwan, Car Park, 1999, Watercolor marker with ink on paper, 14″x11″. Collection of Leslie Lohman Museum.

Michael Kirwan, Car Park, 1999, Watercolor marker with ink on paper, 14″x11″. Collection of Leslie Lohman Museum.

That’s very inspiring to see, all the wonderful work together in one room. How do you think the viewing experience differs from a more mature viewer to a younger one? I think there are definite differences, I think older gay men are more interested in what I just described, sexual acts being portrayed. The older men are still interested in the bad boy aspect of it. The look, “I’m here in this gallery, and I’m looking at men fucking, and sucking, and having sex.” Young boys have had access to this since they learned how to turn on a computer, so it’s a very different thing. So young boys want to see the line quality, they want to see the design quality, they want to see how the drawing is positioned on the paper, they are interested in it as art already. We are not having to sell them that aspect of it. A lot of people will be disappointed it isn’t more of a jerk-off show, but it isn’t, and I’m hoping that some of the museum aspect will rub off on those who come to see a sex show. You can see a sex show at home and you can also see a lot of the more graphic artists like The Hun and Etienne, the ones that do have very graphic pieces in the show, I mean my god you can see stuff that would curl your hair.

What pornographic materials did you use to masturbate when you were young? The ones I’ve described, because that’s all there was. I mean that was it. If there had been DVD. If I had the money, and a television set, and a place to watch it, certainly. But it was fine, I think that, for the men of my generation, a couple generations really, these magazines taught us to use our imaginations. Like reading porn fiction taught you to visualize and by the time this other stuff came, you were kind of okay, it wasn’t as thrilling as the magazines had been because it wasn’t as forbidden.

Yeah the magazines are a treat.

Kevin King (Beau), Pinned, 1997, Acrylic on paper. Collection Leslie-Lohman Museum, Founders’ gift.

Kevin King (Beau), Pinned, 1997, Acrylic on paper. Collection Leslie-Lohman Museum, Founders’ gift.

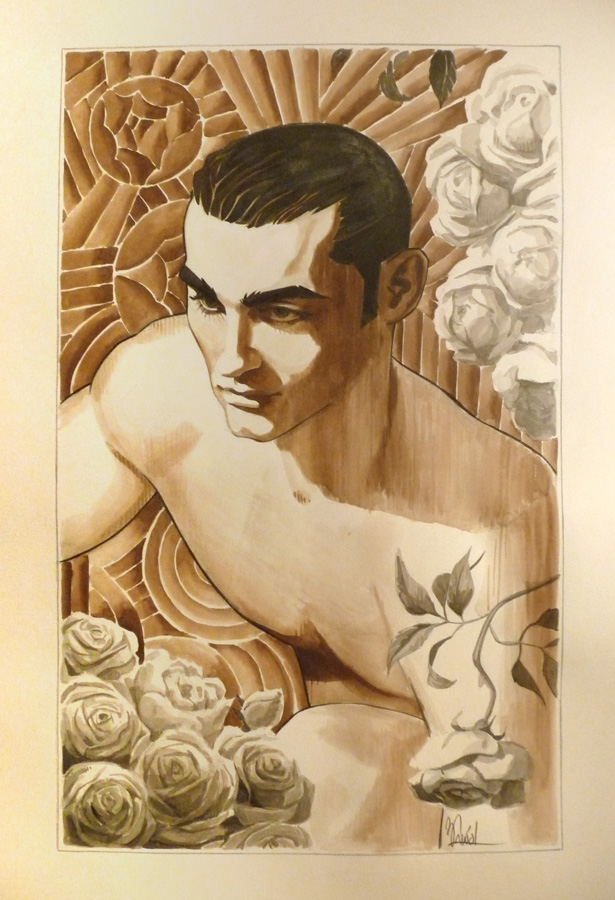

Benôit Prévot, John Roses, 2013, Ink and pencil on paper, 11.5″x8.5″. Courtesy of the artist.

Benôit Prévot, John Roses, 2013, Ink and pencil on paper, 11.5″x8.5″. Courtesy of the artist.

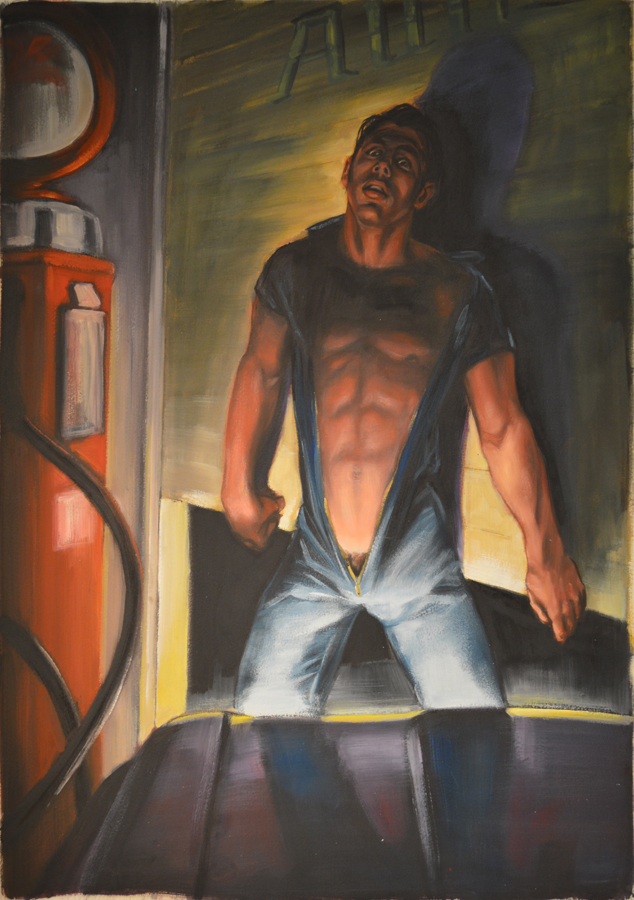

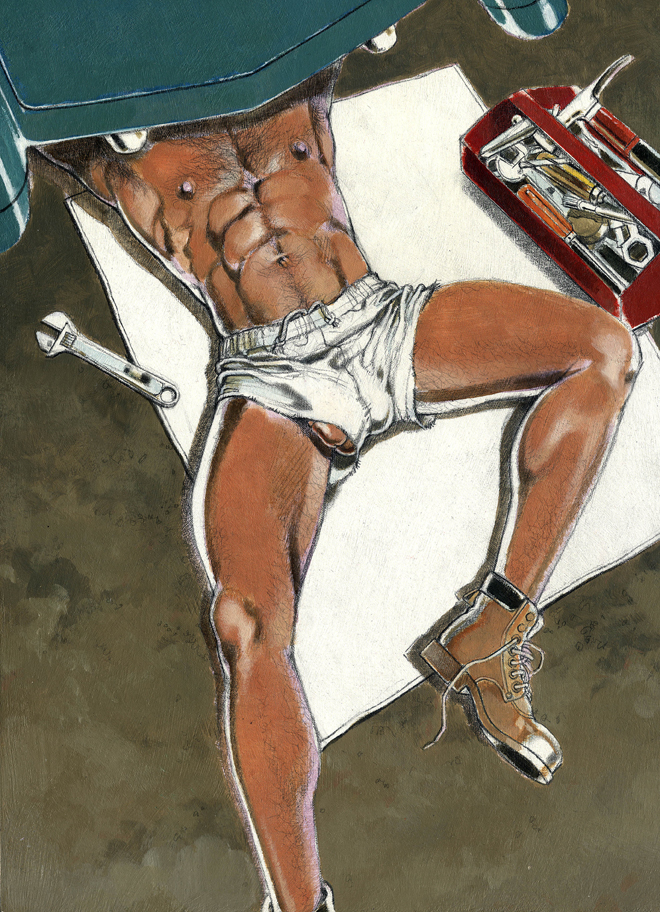

Kent, The Mechanic, 1992, Acrylic and pencil on illustration board, 13″x9.75″. Published in MEN November 1992. Courtesy of the artist.

Kent, The Mechanic, 1992, Acrylic and pencil on illustration board, 13″x9.75″. Published in MEN November 1992. Courtesy of the artist.

Antonio Lopez, Mike Haire 1, 1983, Watercolor and pencil on paper, 23″x15″. Courtesy of the Estate of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos.

Antonio Lopez, Mike Haire 1, 1983, Watercolor and pencil on paper, 23″x15″. Courtesy of the Estate of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos.